- Duration of Spartan hegemony in Greece: (404 BCE – 371 BCE)

The outcome of the Peloponnesian war in favor of Sparta, strong with Persian support, allowed the latter to place itself legitimately as the sole hegemonic force within the Greek landscape, giving rise to a period of “Spartan hegemony” in Greece from the 404 BC to 371 BC, the year of the battle of Leuctra, which will lay the foundations for the period of “Theban hegemony”, which will go from 362 BC to 346 BC and will be closed by the rise of Philip II of Macedonia.

It will be Lisandro, a Spartan warrior of noble origins, who will have command of the city (Sparta, around 440 BC – Aliarto, 395 BC), in the period from the end of the Peloponnesian war until the early stages of the Corinthian war, during the which will find death, to lead the city of Sparta to its most important moment in the Greek world, which will last for a period of about 9 years.

The period of Sparta hegemony resumed in some areas the models of power that had been typical of the imperialism of Athens but presented authentic points of difference with respect to the latter.

The Spartans sent governors to each city, which they would be called “Harmost” (in ancient Greek: “ἁρμοστής”, written in Latin characters “harmostés” (armostes), and which would mean “governor”; this word would derive from the Greek “ἁρμόζω “= join with me, prepare, dispose), endowed with full powers, neglecting the fact that the social base on which the Spartan power would have laid the foundation should have been wider compared to a few thousand Spartans, moreover committed to containing the population group of helots.

To aggravate the position of the Spartan power base there was also the fact that, with the lack of a powerful Athens, there was no fear of Athens itself which had forced many Greeks to accept the Spartan commands.

The Cinadon conspiracy

To make the Spartan hegemony tremble was first the conspiracy of Cinadon, of 398 BC: Cinadone (Κυνάδων, Kynádon) was in fact a Spartan rebel, who attempted a coup d’état during the reign of Agesilaus II.

Cinadone made the mistake of revealing part of his plans or intentions of rebellion to a friend, during a ritual of sacrifices conducted by the king; so it was that “the friend” told the Ephori the intentions of Cinadon, who with a trap led Cinadone out of Sparta, pretending to have entrusted him with an important mission, where he was arrested instead. Cinadon was forced to reveal every detail of the conspiracy and its accomplices; once captured, they were all obliged to run continuously chained around the agora, probably until their death.

The obstacles and the end of the Spartan hegemony

Subsequently the Corinthian war (395 BC – 388 BC) where Sparta will face a coalition formed by Athens, Thebes, Argos and Corinth and the wars with the Persians, will represent an enormous obstacle to the Spartan aims: despite the victories obtained in the past by the king of Spartans Agesilaus in fact, Sparta suffered a significant naval defeat by the Persian Empire in 386 BC, which will lead to the peace of Antalcidas, and consequently to the limitation of Spartan influences to the Aegean alone.

The characteristics of Spartan expansionism in the 4th century BC

As mentioned before Sparta will send governors and military principals in many Greek cities, some of them in Asia Minor, even going as far as to support the uprising of Cyrus the Younger in 401 BC, and thus attracting the irritated attention of the Persian emperor Artaxerxes II.

The expansion of the Spartan influence, which will eventually reinforce its positions, will also take place in central Greece, the northern Aegean and Sicily, where the Spartans will forge important relationships with a view to opposing the Carthaginians, in particular with the old tyrant, Dionysius of Syracuse.

In general we could talk about Spartan power and influence by observing how the latter will be the substitute for the power vacuum generated after the disappearance of Athenian imperialism.

The expansion of influence and Spartan power will in any case bring numerous frictions and will come to a standstill, and will begin its demotion, with the war of Corinth, which in fact sees its roots in the opposition and in the desire to contrast to Sparta’s expansionism.

Sparta intervened militarily within Asia Minor, officially under the pretext of acting as a shield towards the self-determination of the Greek polis, thus defending them from the Persian danger, finally coming to open a real military conflict with the satrap Tissaferne; the latter was able to show the deficiencies of Sparta, who even went as far as robbing the allied cities to raise funds, in conflicts carried out outside Greece, as well as in the medium and long term.

The first part of the war ended with the Spartan success: in 396 BC in fact Agesilaus, king of the Spartans, succeeded in defeating the army of Tissaferne in Sardis, so that the Persian emperor sent to treat the peace with Sparta a substitute satrapo, called Titrauste.

In the peace negotiations Titrauste proposed to Sparta the payment of a tribute to Persia in exchange for the independence of the cities of Asia Minor, finding the rejection of the Spartans.

Thus it was that Sparta began to prepare a second phase of the conflict with the aim of separating the center of the Persian empire with Asia Minor.

Given the risk posed by the Spartan policy pursued by Agesilaus in Asia Minor, the Persian emperor strove to favor the Athenians as much as possible, for example with the appointment in 397 BC of Conon as admiral of the Persian fleet.

The support of the Persian emperor in the anti-partisan movements became increasingly concrete, for example by sending Timocrates of Rhodes, along with a large amount of money (50 talents) to be allocated to the rebels; the anti-partisan aid arrived especially in the cities of Thebes, Corinth and Argos.

These events reached the peak of their consequences in 395 AD, when the Thebans decided to intervene during a territorial dispute between Locresi and Focesi, starting the Corinthian War.

The city of Sparta chose to support the focesi, thus placing itself against the faction of Thebes, which supported the focesi, in turn supported also by Athens, Argos and Corinth.

The death of Lysander

After arriving before Pausanias in the war zone, Lisandro will convince the citizens of Orchomenus to ally with the Beoti, thus going to the side of the Spartans; after doing so he went to Haliartus, accompanied by his troops over by a division of Orcommenus. He then sent a messenger to Pausanias, informing him to join him, also announcing that he would be under the walls of Haliartus at dawn.

The messenger, however, was intercepted by the Thebans who then moved to receive reinforcements as soon as possible. Lysander then arrived under the city of Haliartus, and although he lacked the help of Pausanias, he decided to attack the city; the Thebans, however, were ready to attack and as soon as they arrived at the gates of Haliartus the Thebans made a sortie, finding Lysander unprepared, and killing him along with his men, while a part of the troop withdrew.

It was 395 BC: Lysander died around the age of 45.

The Spartan defeats in the Corinthian war

As for the Greek polis in the minor Asia, Conon did his best to allow the polis to enjoy great freedom and autonomy, thus inaugurating the alliance between Athens and the Persian empire; it was thanks to this alliance that Athens had at its disposal the financial means of the great Persian king, who allowed him to build again the great walls of Athens and to reforest the Piraeus.

In 392 BC Corinth began a merger with Argos, creating a new supra-Citizen entity to cope with Spartan military interference within the Peloponnese, thus giving a second jolt to Spartan hegemony.

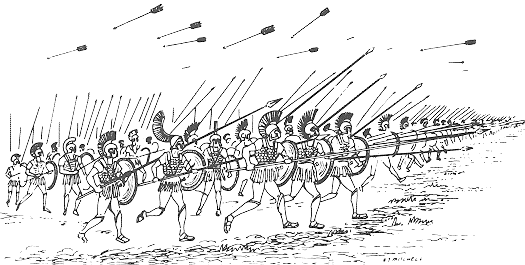

In the area of Lechaeum the Spartans, who had previously conquered numerous strongholds under Agesilaus’ leadership, collecting a lot of loot and various prisoners, were finally repulsed and defeated by the Athenian general Ificrate, famous for his winning deployment of peltasts during the battles, which he was stationed in Corinth, leading an army of mercenaries composed precisely of peltasts (an infantry initially successfully deployed in Thrace, equipped with various javelins to throw and a wooden shield, usually covered with a type of leather) called “pelta”) and gymnastics (a type of light infantry armed with a light shield and a bow, a javelin or a sling).

The end of the Corinthian war and of the Spartan hegemony

Attempts at peace began to take shape when Sparta hosted a polis congress to find a suitable solution to reconcile Greece by putting the autonomy of the various Greek polis as its basic principle; however, no agreement was found that would satisfy the major players in the conflict.

The Persian emperor, however, decided to change his mind once again: the agreement with Athens was in fact allowing it to be reborn and resume its expansionist ambitions behind the leadership of Conon and Trasibulo.

Unlike Athens, in fact, Sparta became the guardian of the balance of power and the status quo, as well as guarantor of the city’s autonomy of the Greek polis.

Thus it was that the peace of Antalcida (387/386 BC) was reached through the summoning of the interested parties to Sardis: the peace treaty established the independence of the Greek poleis with the exception of Lemnos, Imbros and Scyros (they would have remained under Athenian control), but it would have sanctioned the Greek renunciation of the conquests carried out in the Aegean, which would have passed under the Achaemenid empire; moreover, the great king would have retained control of Cyprus and the cities of Ionia and Clazomene. Among the common points of the treaty was respect for the treaty; whoever violated the treaty would have sanctioned the empire’s immediate declaration of war to the poleis that would have joined the violation, “by sea and by land, with ships and with money”.

The peace of Antalcida represented the compromise between the Persian aspirations of hegemony in Asia and the Spartan role of defender of the Greek poleis autonomy, obtaining, with the ratification of the treaty, the role of guardian of peace.